The Brock University Film Society operated as a monthly series this last year, 2022-2023.

Our line-up consisted of the following films:

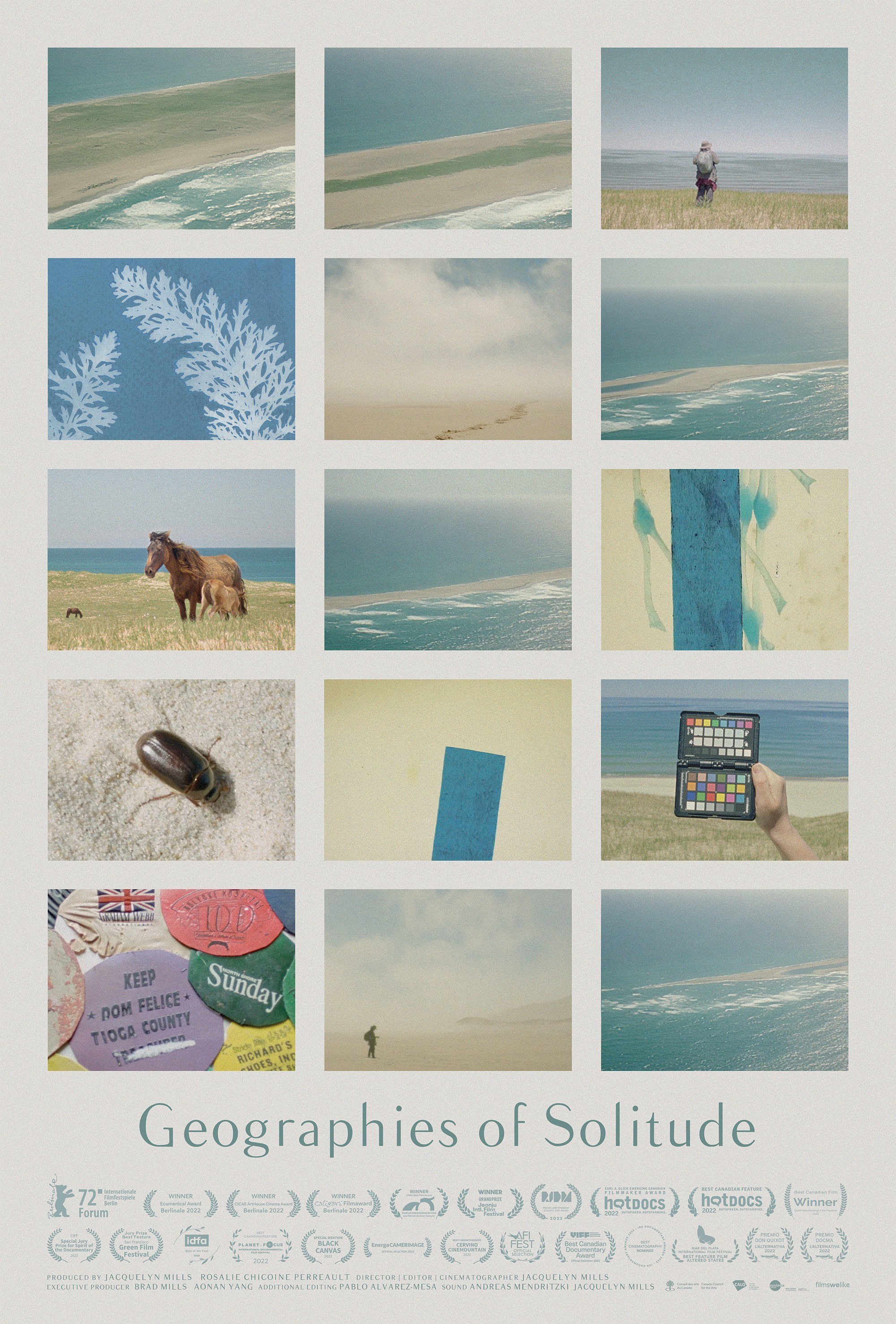

March 9, 2023—Geographies of Solitude (2022), dir. Jacquelyn Mills

In a recent interview on The Ezra Klein Show, in an episode titled “The Art of Noticing—And Appreciating—Our Dizzying World," the American poet Jane Hirshfield discussed her pronounced shift toward environmental issues and what we might call an overt eco-poetic sensibility. This development was prompted by the ever-increasing urgency of the climate crisis, of course, but it was also tied to a growing awareness on her part of the staggering inter-connectedness of life on earth. Hirshfield noted that none of this was entirely new—she’d been an active part of the very first Earth Day proceedings back in 1970 and had long had an attraction to nature, in spite of her New York upbringing—but it had become more prominent in her work in recent years as climate change had become a clear and present danger.

Zoe Lucas is a Canadian naturalist who experienced an epiphany in 1971 when she first visited Sable Island, Nova Scotia, a rather large, but extremely narrow spit of land—40 kilometres long and 2 kilometres across at its widest point—that sits 100 kilometres off the mainland. Lucas had gone to the island to see its famous wild horses, but the experience turned out to be life-changing. She visited the island repeatedly over the next several years, and in the early 1980s she relocated to Sable permanently. Lucas arrived as an art student from the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, but within a few years she’d become an amateur naturalist—a particularly passionate and committed one. As she’s noted, the thrill of learning things directly, instead of reading about them in books was something she found unbelievably compelling. Lucas has been the island’s sole year-round human inhabitant for over 40 years. Over time, as oil, debris, and especially plastics have washed ashore in greater and greater quantities, wreaking havoc on Sable, its ecosystem, and the waters that surround it, she’s become the island’s steward, as well as a highly respected environmental researcher and sentinel.

Jacquelyn Mills is a talented Canadian filmmaker with a poetic sensibility. Her film Geographies of Solitude is a remarkable account of Zoe Lucas and her profound relationship with Sable Island—an experimental documentary that is “part nature film, part biographical portrait,” as the critic Ben Kenigsberg has noted. At one point in the film we hear audio of Lucas addressing an audience in 2015. “So, I’m not going to give you a straightforward talk about the natural history of Sable Island. This is more about experiencing Sable.” The same could be said of Geographies of Solitude. This is not a conventional film about the natural history of Sable Island. This is a film about experiencing Sable, about experiencing the richness, diversity, and complexity of its ecosystem, about submitting to its majesty, its subtleties, its cruelty, and its peculiar genius, and about the art and science of noticing—and appreciating—its dizzying and awe-inspiring world.

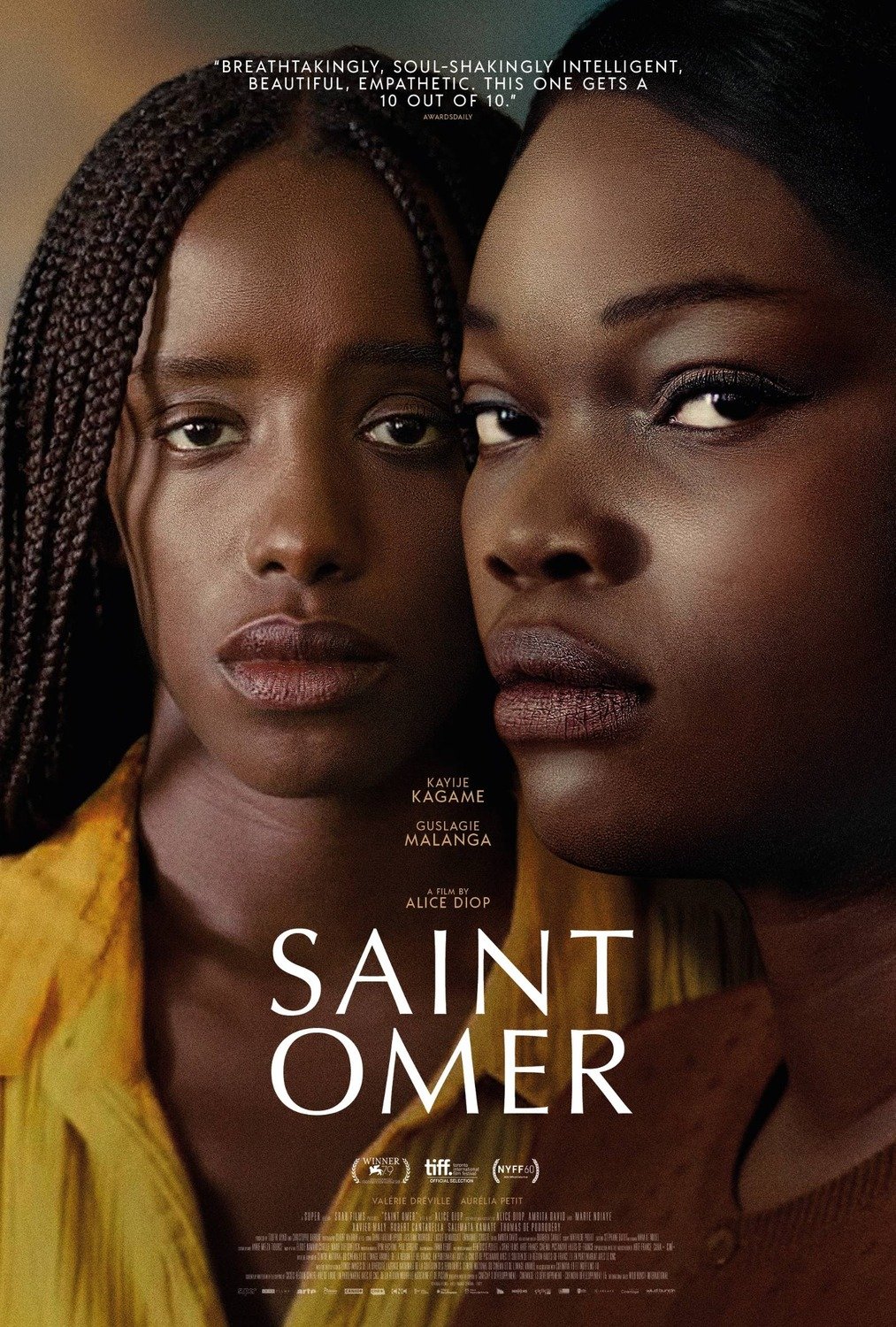

February 9, 2023—Saint Omer (2022), dir. Alice Diop

The gifted French director Alice Diop is primarily known as a documentarian whose films often display an interest in the greater Paris region—from which she hails—and a sociological sense of its complexities, its tensions, and its challenges. Diop is also of Senegalese descent, so, perhaps not surprisingly, she’s often been attracted to the lives and the narratives of recent immigrants. This was certainly the case with her first major documentary, On Call (2016), which dealt with a doctor in suburban Paris whose practice specialized in attending to recently arrived refugees from around the world. Diop spent a year at the clinic researching the story and taking notes while the doctor, together with a psychiatrist, took on the Sisyphean task of healing the bodies, minds, and souls of this constant flow of new patients. Eventually she found a way to make a film about the clinic while doing everything she could to respect the dignity of her subjects.

We (2021), Diop’s breakthrough film, was a sweeping study of Paris, one that traced the path of a rail line that traverses the entire region, finding stories in its suburban districts at either end of the line, giving voice to characters and ways of life across classes that might otherwise be neglected. At first, Diop maintains an observational distance to her subject matter, but gradually her voice begins to make its way into certain scenes, her family—and especially her relationship with her father—becomes an important chapter in the film, and eventually the director herself appears on camera, personalizing the film, introducing the “I” of the filmmaker into We.

Diop’s latest film, Saint Omer, is a fictional work in an established genre—the courtroom drama—but one that was pulled from the headlines. The film deals with the story of Laurence, a highly educated immigrant woman from Senegal who is accused of having committed infanticide in a case that winds up dredging up issues of gender, race, and class, as well as France’s colonial past and its post-colonial present. Saint Omer’s protagonist is a young woman named Rama, a novelist who also happens to be of Senegalese descent, and who attends the trial obsessively, hoping to use some of the material in an adaptation of Medea that she is writing. Like Rama, in 2016 Diop found herself obsessed with a very similar trial that also involved a highly educated Senegalese immigrant accused of infanticide and that happened to take place in a town named Saint Omer. The product of Diop’s obsession is Saint Omer, a film that, according to Michael Phillips of the Chicago Tribune, has taken “a straightforward premise [and transformed it] into the stuff of unassuming, unexpected and authentic poetry.”

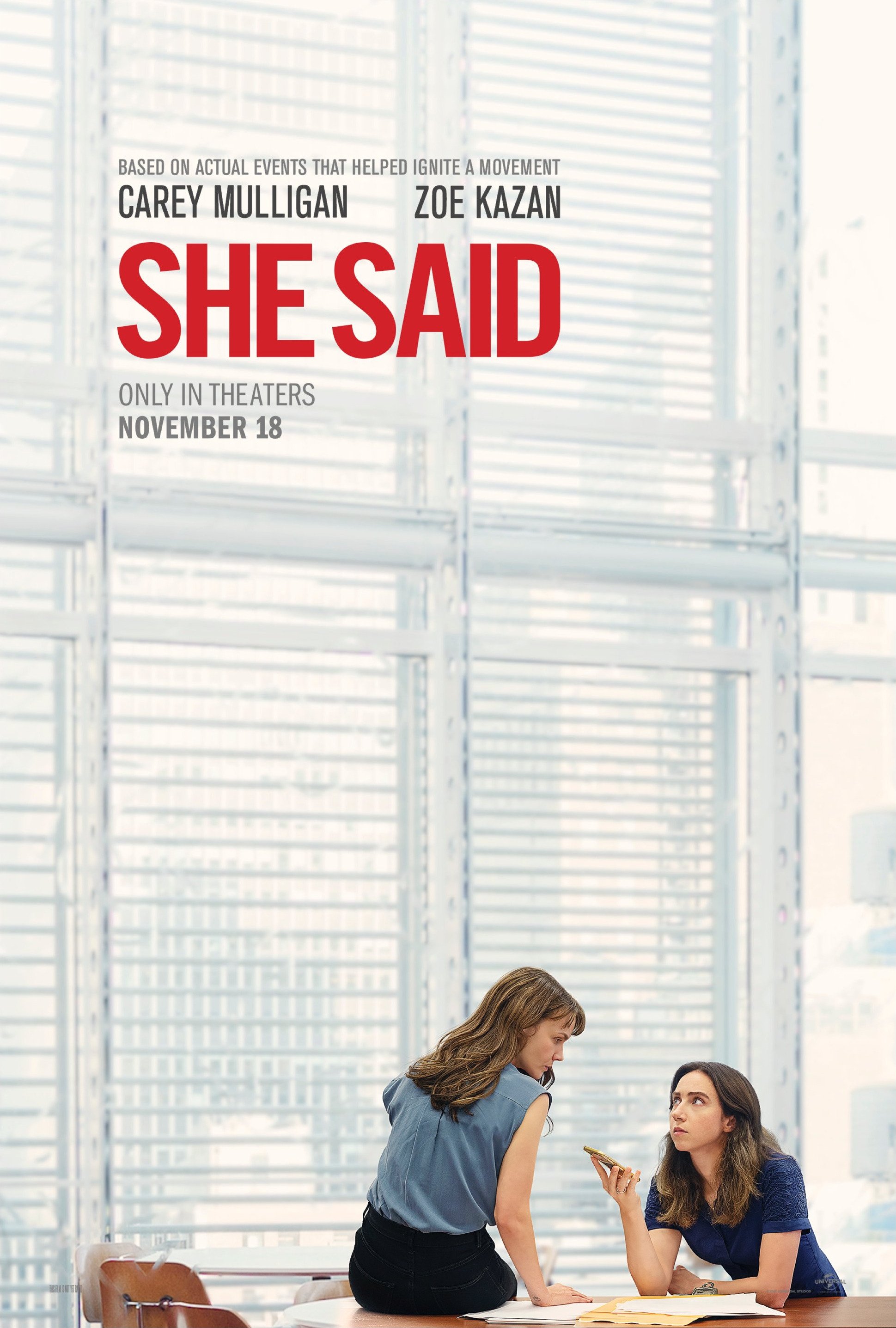

January 19, 2023—She Said (2022), dir. Maria Schrader

The investigation into Harvey Weinstein and the decades-long pattern of sexual harassment, sexual abuse, and rape that accompanied Weinstein’s rise from a Hollywood outsider to the ultimate Hollywood power broker remains one of the signal accomplishments of the #metoo movement.

Famously, after years where Weinstein managed to avoid scrutiny and remained one of the most powerful and feared figures in the entertainment industry, two major investigations were finally able to gain traction in the late-2010s, uncovering evidence and successfully collecting the testimony of victims in a way that previous investigators had been unable to. In both cases, not only were Weinstein’s abuses revealed in great detail, but the widespread use of non-disclosure agreements by men in positions of power in order to dispel accusations of sexual harassment was laid bare.

One of these investigations was led by Ronan Farrow at The New Yorker. The other was conducted by Megan Twohey and Jodi Kantor at The New York Times. Together, the two investigations helped bring Weinstein’s reign of terror to an end in the fall of 2017. Both investigations won Pulitzer Prizes, and both resulted in bestselling, highly acclaimed books in 2019: Farrow’s Catch and Kill: Lies, Spies, and a Conspiracy to Protect Predators and Kantor and Twohey’s She Said: Breaking the Sexual Harassment Story That Helped Ignite a Movement.

She Said, directed by Maria Schrader, is a biographical drama based closely on Kantor and Twohey’s groundbreaking work. It’s also a great newsroom drama in the tradition of films like Tom McCarthy’s Spotlight (2015), which tackled the Boston Globe’s investigation into child sex abuse committed by numerous Roman Catholic priests in the Boston area, and Allan J. Pakula’s All The President’s Men (1976), which dealt with Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward’s Washington Post investigation into the Watergate scandal.

In fact, She Said plays a lot like a feminist All The President’s Men. Zoe Kazan and Carey Mulligan bring grit, determination, and empathy to the roles of Kantor and Twohey, and they’re complemented by a fantastic cast, including Patricia Clarkson as Rebecca Corbett, a rigorous but supportive editor, and André Braugher as Dean Baquet, the Times’s former executive editor.

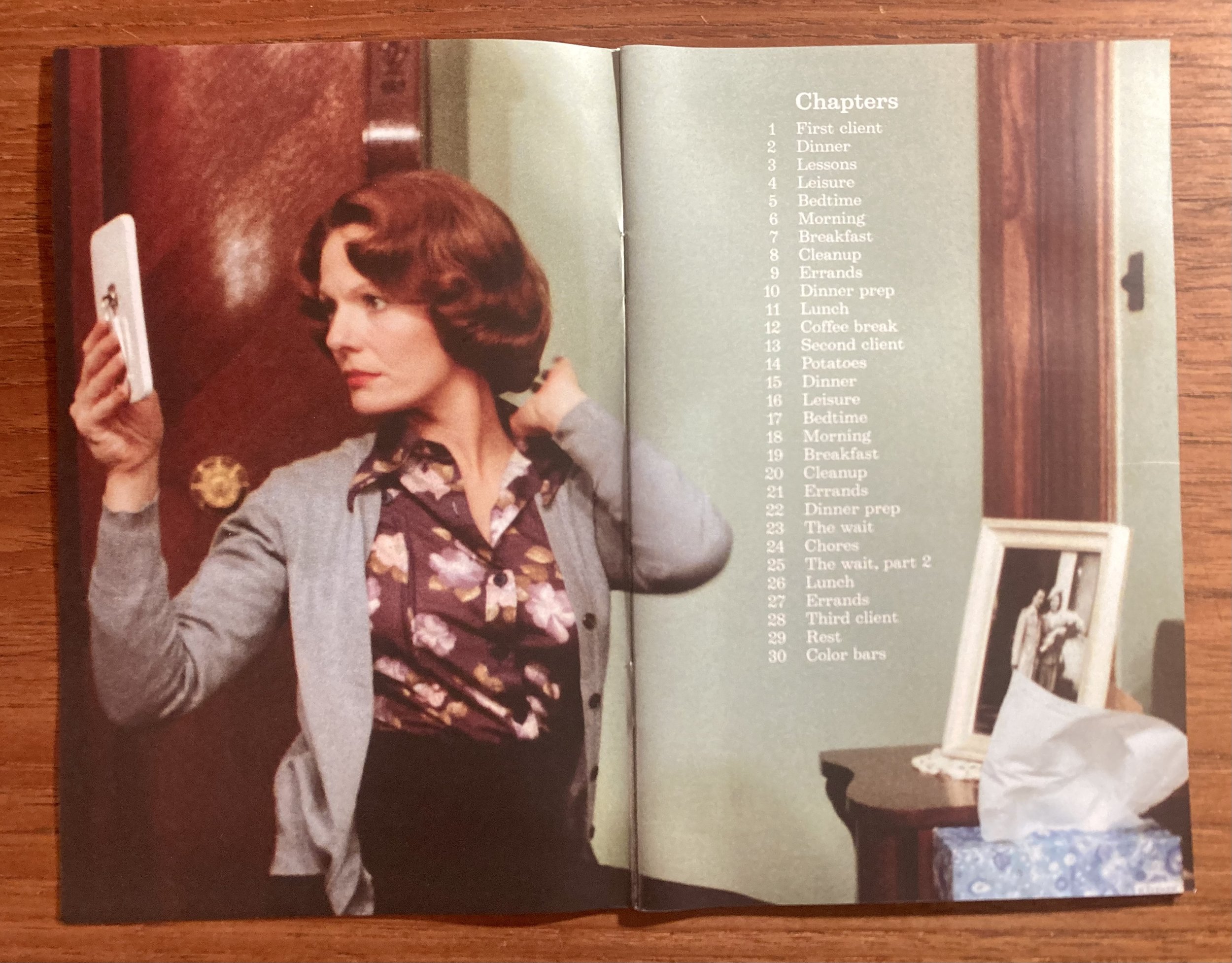

December 8, 2022—The Eternal Daughter (2022), dir. Joanna Hogg

As some of you may know, the British director Joanna Hogg is a particular favourite here in the offices of the Brock University Film Society. We’ve been following her work with interest and admiration for several years now. Though Hogg’s career in film and television dates back to the 1980s, she was mostly involved in the latter, television, until about 15 years ago, when she began to make her presence known on the international cinema stage.

From the start of this most recent chapter, Hogg has specialized in unconventional family melodramas, ones where the tensions and conflicts are often much more subtle, much more nuanced than we typically associate with the genre, but no less poignant, no less affecting. Archipelago from 2010 was a standout in this regard. It was so mysterious, so hard to pin down (Who are these people? What are their backstories? Where in god’s name is this film set?), and yet so resonant.

Archipelago featured Tom Hiddleston, and Hiddleston was something of a muse for Hogg, starring in her first three feature films in the years before he became a fixture of the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

Since then, Hogg has returned to her original muse, Tilda Swinton, the phenomenally talented actor who appeared in Hogg’s graduate student film Caprice back in 1986, when both women were at the very beginning of their respective careers.

Hogg truly came into her own as a director with her last two films, a highly autobiographical diptych about a young woman trying to find her identity as a film student in the 1980s: The Souvenir (2019) and The Souvenir: Part II (2021). Both films starred the fantastic Honor Swinton Byrne as Julie, the character based on the young Joanna Hogg. Nearly as important, however, was the actor who played Julie’s mother, Rosalind—none other than Tilda Swinton, Honor Swinton Byrne’s real-life mother.

Hogg’s latest film, The Eternal Daughter, is the third part in the series. Julie is back, but is now a middle-aged director. Rosalind, too, is back, but has aged accordingly. And the two women find themselves in a film that is both an unconventional family melodrama and a ghost story of sorts. While the film has been described as “eerie,” “haunting,” “lovely,” “moving,” and “sly,” a significant part of its magic once again has to do with casting. As one critic put it, "Hogg’s greatest stroke in The Eternal Daughter is her casting of Swinton in both lead roles. Swinton is a wonderful chameleon and while she can go as big and showy as any Oscar contender, she is also a brilliant miniaturist.”

That’s right—Swinton plays both Julie and Rosalind, and the result is a truly breathtaking performance, one that stunned audiences when the film premiered at the Venice Film Festival earlier this year, one that is yet another highlight in an acting career that has been chock full of them.

——

Speaking of unconventional family melodramas, just last week Sight & Sound released the latest edition of its famous list of the Greatest Films of All Time. Every ten years Sight & Sound polls critics, scholars, programmers, curators, and archivists on their Top Ten films, the results are tallied, and a list of the Greatest Films of All Time is produced. This year the number of experts surveyed grew substantially—from 846 in 2012, to 1,639 in 2022—and the results of the new poll were dramatic.

Among other things, the list now has a new #1 film: Chantal Akerman’s 1975 hyper-realist art house classic Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce 1080 Bruxelles. Akerman’s film first appeared on the list in 2012, when it was expanded to 100 titles—it showed up in the #36 spot. How does one account for Jeanne Dielman’s truly remarkable ascent? Among other factors, Laura Mulvey, the esteemed British film scholar, has noted an influential film series called “A Nos Amours” that was held in London between 2013 and 2015, where a complete retrospective of Akerman’s work was held—the first one ever mounted. One of the co-curators of the retrospective was our friend Joanna Hogg.

November 17, 2022—Decision to Leave (2022), dir. Park Chan-Wook

His career got underway a decade earlier, but for many people in the West, Park Chan-wook’s Oldboy (2003), his gritty, utterly captivating neo-noir thriller was an introduction to a bold new directorial talent. It also served notice that 21st-century South Korean cinema was a force to be reckoned with. In fact, in some ways, with its craft, its vision, and its cruel ironies, Oldboy anticipated the blockbuster success of Bong Joon Ho’s Parasite, which took the world by storm in 2019-2020.

In 2009, Park followed up on the success of Oldboy up with an offbeat vampire film called Thirst, one whose inspiration came from Émile Zola’s Thérèse Raquin, of all places, indicating his ambitions. Speaking of ambitions, Park’s next film was his first venture into English-language filmmaking: Stoker (2013), starring Mia Wasikowska and Nicole Kidman. It was written by the actor Wentworth Miller (Prison Break), who described it as part horror film, part family melodrama, part psychological thriller, and it took its inspiration from both Bram Stoker and Alfred Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt.

And in 2016, Park returned with The Handmaiden, a twisted and fascinating study of class, sex, gender politics, and colonialism in 1930s Korea, when it was under Japanese rule. Here, too, Park displayed a penchant for audacious adaptations. In this case, the source material was Sarah Waters’s Fingersmith, set in Victorian Britain, and Park found a way of creating a connection between these vastly disparate locations and time periods through the aristocratic taste for British-inspired architecture and manners that was in vogue in Korea at the time.

Now, Park is back with one of his most acclaimed films yet, Decision to Leave, a Hitchcockian psychological thriller that has been widely hailed as a “masterpiece.” The narrative involves a suspicious death, a police investigation, a mysterious and beautiful widow, and a detective who falls hopelessly, obsessively in love. As Manohla Dargis of the New York Times put it: “Park’s most obvious touchstone is Vertigo, Hitchcock’s sublime 1958 l’amour fou about a detective who falls in love with a woman he thinks he’s lost only to find and lose her again.”

The more I read about this film, the more I find myself thinking of the line from the old Chet Baker song: “let’s get lost.” Personally, I can’t wait.

November 10, 2022—Triangle of Sadness (2022), dir. Ruben Östlund

The Swedish director Ruben Östlund burst on to the world cinema scene in 2014 with Force Majeure, a highly idiosyncratic family melodrama whose narrative depicted one tumultuous week at a luxury ski resort high up in the French Alps. The film’s Swedish title, Turist (or “Tourist”) was simultaneously more to the point and rather vague. The film’s English title, and the one that was used more commonly around the world, was more suggestive, alluding to the avalanches (both “controlled” and somewhat out of control) that unsettled what was supposed to be an idyllic Alpine getaway for an outwardly ideal Swedish family.

Since then, Östlund has further reinforced his reputation as one of top directors in contemporary cinema. In fact, he’s won the Palme d’or, the top prize at the Cannes Film Festival, with each of his last two films. In doing so, he’s joined an extremely select group of filmmakers who’ve won the award twice, one that includes Francis Ford Coppola, Michael Haneke, the Dardenne Brothers, and Ken Loach.

The first of Östlund’s Palme d’or winners was The Square (2017), an absolutely savage skewering of the contemporary art scene, its ties to the world of Big Business, especially advertising, and the buzzy mediascape that is so crucial to its viability—and so capable of tearing it all apart.

Östlund’s most recent success is Triangle of Sadness, and this time the target of his lethal form of satire is the billionaire class, those sycophants and glitterati who congregate around them, and those who serve them, with a particular focus on today’s superyacht culture. Prepare yourselves for an unforgettable cruise, and, remember, a flotation device can be found underneath your seat cushion should we encounter turbulence.

October 27, 2022—Moonage Daydream (2022), dir. Brett Morgen

Our BUFS 2022-2023 season got started on a “particularly flamboyant note” a few weeks ago, when we screened Valérie Lemercier’s truly outrageous Aline, the French filmmaker’s totally unauthorized biopic of Celine Dion.

Well, we might be dealing with a very different type of film, but, once again, popular music is of the essence and the flamboyance factor is not letting up a whit. That’s because our next film is Brett Morgen’s Moonage Daydream, his magical, mysterious, at times hallucinatory, but ultimately moving rockumentary about the late, great David Bowie.

One of the peculiarities of the history of the rockumentary is that the artist who was arguably the artiest, most theatrical, and most cinematic rock star of his time never got the full-blown, artistically significant popular music documentary he so deserved. Frankly, it’s surprising Bowie didn’t direct or collaborate on such a film himself, especially given his interest in film and its history, in acting, in music videos, and in the creation of experimental cinema and video.

Sure, there were exceptions, like D.A. Pennebaker’s 1979 film Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars, a record of Bowie’s outlandish 1973 tour from one of the pioneers of the genre,* and one that provided Morgen with some choice material, but such films lacked the scope that might have captured Bowie’s constant shape-shifting, his gender-bending, and his genre-blending. There were also countless documentary profiles, mostly of the made-for-TV variety. But an ambitious, sweeping, artful documentary eluded Bowie—until now, six years after his death.

Brett Morgen has been a leading documentary filmmaker for at least 20 years, since the time of The Kid Stays in the Picture (2002), his fascinating portrait of Robert Evans, the legendary film producer and “godfather of the New Hollywood.” Since then, some of Morgen’s most notable films have been rockumentaries, like Crossfire Hurricane, his 2012 account of The Rolling Stones circa 1972, and Cobain: Montage of Heck (2015), his devastating biography of Kurt Cobain. And in the remarkable story of David Robert Jones, the artist and musician who transformed himself into Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane, the Thin White Duke, and, most importantly, David Bowie, Morgen appears to have found his ultimate subject. At the very least, Bowie seems to have unleashed Morgen’s daring archival collage aesthetic to its fullest extent.

The result? Well, as Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian has put it, “Brett Morgen’s Moonage Daydream is a 140-minute shapeshifting epiphany-slash-freakout leading to the revelation that, yes, we’re lovers of David Bowie** and that is that.” Or, to word things a little more concisely, as The Globe and Mail’s Brad Wheeler did: “Freak out in a moonage daydream, oh yeah.”

*“Penny,” as he was known by his friends, was also responsible for Dont Look Back (1967), his seminal observational documentary about Bob Dylan’s 1965 UK Tour, and Monterey Pop (1968), his equally era-defining study of the 1967 Monterey International Pop Festival and the Summer of Love.

**Ed.: or we should be.

September 15, 2022—Aline (2021), dir. Valérie Lemercier

The Brock University Film Society is back for its 2022-2023 season, and things are starting off on a particularly flamboyant note.

Get this: "For Aline Dieu, nothing in the world matters more than music, family and love. Her powerful and emotional voice captivates everyone who hears it, including successful manager Guy-Claude Kamar, who resolves to do everything in his power to make her a star. As Aline climbs from local phenomenon to best selling recording artist to international superstar, she embarks on the two great romances of her life: one with the decades-older Guy-Claude and the other with her adoring audiences.”

Any of this sound vaguely familiar? Any of this sound like it could be "a fiction freely inspired by the life of Celine Dion"? Well…

Valérie Lemercier's Aline was one of the biggest sensations of the 2021 Cannes Film Festival. It garnered 10 nominations at the 2022 César Awards (France's Oscars) for everything from Best Costume and Best Production Design, to Best Director and Best Film). And it took home one major prize: Best Actress (awarded to Lemercier herself). It was also one of the most controversial films of the year.

What was all the fuss about? Lemercier dared to make an unauthorized biopic based on the life of Celine Dion. She dared to play Celine herself. And, not only that, but she had the audacity to play Celine at virtually every stage in her life, from the age of 5 till the age of 50 (!). How? You'll have to see it to believe it. Why? You be the judge!

Critics were hotly divided on Aline. Many were appalled. Many others were astounded. Kyle Buchanan, reporting on the Cannes Film Festival for the New York Times, perhaps put it best: "You see a lot of nervy things at Cannes, but this surely takes the cake.”

At the very least, Aline seems destined to be a cult classic (if it isn't already). The kind of film that inspires fans to learn all the lines, encourages them to get in costume, and emboldens them to belt out their favourite Celine numbers (as if they don't do that already!).

Please join us for a singular experience.