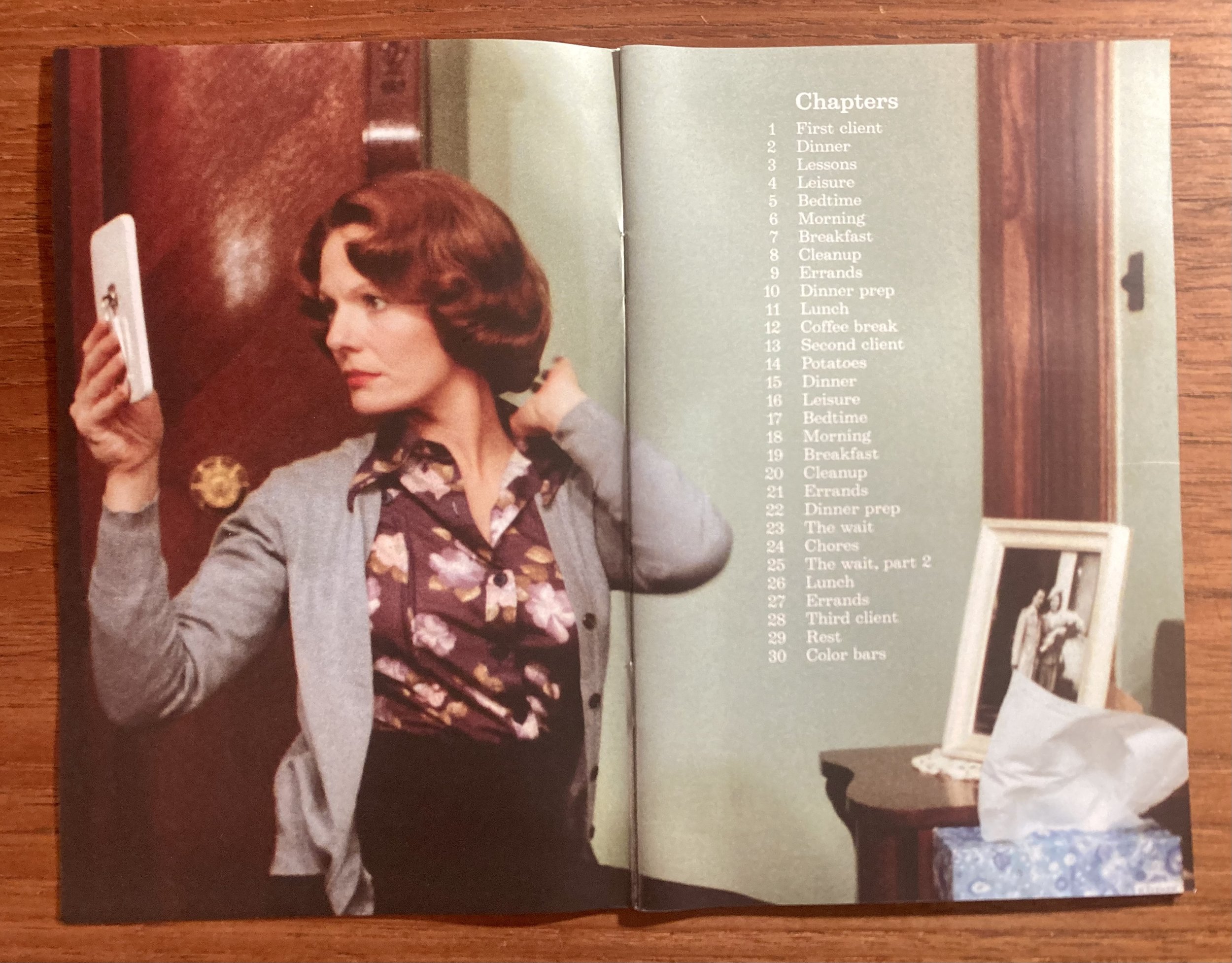

fig. a: ready for her selfie: Jeanne Dielman, as played by Delphine Seyrig, as she appears in the DVD edition of Jeanne Dielman, 23, qui du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (Criterion Collection)

Shaken, Not Stirred

Powerful tremors have been felt in the realm of film for several days now, and the reverberations, and accompanying debates, are likely to last for quite some time. At least ten years.

Thankfully, this time around the cause isn’t another disturbing scandal. It isn’t a mega-merger. It’s not even something having to do with the Marvel Cinematic Universe. It all has to do with the release of the latest edition of the Sight & Sound survey of the Greatest Films of All Time.

The top film is a non-Hollywood film for only the second time in the history of the survey! Not only that, but it was directed by a woman! It’s also a minimalist and hyperrealist film—and therefore an outright rejection of the maximalist and fantastic cinema that has reigned supreme at the box office for decades.* And it’s a film that’s almost 3 1/2 hours long!

Just this alone—this bold, new, surprising #1 selection—would have been big news in film circles, but it was hardly the only shocker to be found in this year’s survey. After decades of relative stability—the kind of conservatism we often associate with canon preservation—the foundation of the temple has been shaken. If not an all out revolution, the new poll results certainly amount to a revolt.

Hitchcocko-Wellesians

Sight & Sound, of course, is the film journal of the British Film Institute. In 1952, when Sight & Sound was celebrating its 20th anniversary, its editorial team came up with the ingenious idea of soliciting the opinions of a fairly large group of film critics in determining a list of the most significant films ever made, instead of just coming up with a list on their own from within their own ranks.

Ten years later, Sight & Sound took the same approach to devise a new list, and the exercise has been a decennial tradition ever since. Not only that, but they’ve greatly expanded the scope of their inquiry over the years. By 2012 the list had grown into the 100 Greatest Films of All Time, and those polled began to include a wider array of programmers, scholars, archivists, and curators, in addition to film critics.

A decade ago, the biggest storyline was that Orson Welles’s 1941 epic American tragedy Citizen Kane, the film that had held the top spot since 1962 was dethroned—by Alfred Hitchcock’s mesmerizing 1958 psychological thriller Vertigo. More than one critic referred to this as a “coup” at the time. Others were less dramatic: a “modest revolution,” one critic commented.

Hitchcock had never appeared on the list until 1972, when Vertigo first made the poll in the #12 position. 1982, when it reached the #8 position, was the year that Vertigo’s arrival caught people’s attention and there began to be talk of “the hard work of the Hitchcock critical industry.” Such comments proved prescient.

What ensued was a truly remarkable ascent: Vertigo reached the #4 position in 1992 and the #2 position in 2002, before finally reaching the #1 position in 2012. This year, though Vertigo is no longer in the #1 position, it has only been demoted to #2 (again)—meanwhile, three other Hitchcock thrillers are in the Top 100 for the second time in a row—Psycho (1960), Rear Window (1954), and North by Northwest (1959)—and they’ve all moved up in the rankings.

Enter Jeanne

So what is the film that has crashed the party in such dramatic fashion, making the great leap forward from the #36 position a mere ten years ago, to the #1 position in 2022? Chantal Akerman’s 1975 film Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce 1080 Bruxelles, of course—a film that is so singular, so entirely unconventional, that its title is an address. A very specific one. In Brussels.

fig. b: Jeanne Dielman as she appears on the cover of the DVD edition of Jeanne Dielman, 23, qui du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (Criterion Collection)

This is no Sunset Blvd. (1950), Billy Wilder’s beloved noir study of Hollywood past and present, which held firm on the list at #78. Nor is it Mulholland Dr. (2001), David Lynch’s twisted neo-noir examination of Hollywood, which was another one of this year’s party crashers—moving from the #28 position in 2012, to the #8 position in 2022. Here, the geography is much more specific, and infinitely less glamorous.

In some ways, the fact that Vertigo was displaced by a film like Jeanne Dielman has a certain logic to it. Akerman’s methodical, precisely executed, and utterly fascinating investigation of a woman on the verge of a nervous breakdown, in the midst of a nervous breakdown, and in the immediate aftermath of a nervous breakdown, has everything to do with sex and murder and guilt—three obsessions that were central to Hitchcock’s work.

The film might also be seen as a deconstruction of a police procedural, or perhaps, more accurately, a police procedural turned on its head—where instead of a crime prompting an investigation into what went wrong, here the study of what went wrong comes first, in great detail, covering minutiae that the police and the criminal justice system will likely never understand and that Jeanne Dielman herself might not be aware of.

And, it must be noted, for every person who finds the film “utterly fascinating,” there are ten who find its radical experimentation with cinematic duration to be tedious and exhausting, and 100, maybe 1,000, who’ve never heard of the film, let alone seen it.

There’s no question Chantal Akerman was a director of great significance. There’s no question that the team that created Jeanne Dielman was inspired—especially Akerman, who brought an exacting vision to the project, but also her longtime cinematographer Babette Mangolte, her editor Patricia Canino, her art director Philippe Graff, and Delphine Seyrig, that icon of European art house cinema** whose turn as Jeanne Dielman is quite simply a tour-de-force performance. There’s also no question that placing Jeanne Dielman at the top of the list of 100 Greatest Films of All Time will be seen by many as provocative. As will the inclusion of Akerman’s 1976 experimental documentary News From Home in the #56 position, one of a number of documentaries and experimental films (in this case, the film is both) that now appear as part of a group that had long been dominated by fictional narratives.

Sea Change/See Change?

How is one to account for this sea change? Part of it has to do with the fact that although there are those who would deny it, the history of film just keeps growing and growing, even in the midst of a global pandemic. Every ten years there are so many more films to contend with, many of them notable, some of them remarkable.

Then there’s the sheer number of critics, programmers, scholars, archivists, and curators who are now polled—between 2012 and 2022, this number nearly doubled, from 846 to 1,639. There’s also the issue of demographic change within the ranks of these professions, and thus among those polled by Sight & Sound.

This is also the first Sight & Sound poll of the #metoo and #timesup era, as well as the #blacklivesmatter and the #________sowhite era. There are considerably more women filmmakers on the new list than there were in 2012. And with Claire Denis’s Beau Travail (1997) now positioned at #7, there are suddenly two films directed by women in the Top Ten, when there had never even been one before. Meanwhile, African-American directors appear on the list for the very first time, including recent titles such as Barry Jenkins’s Moonlight (2016—tied for #60) and Jordan Peele’s Get Out (2017—tied for #95), alongside Spike Lee’s Do The Right Thing (1989—#24), Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep (1977—tied for #43), and Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust (1991—tied for #60).

Finally, with the last two polls in particular, there’s been a concerted effort to internationalize the realms of film studies and film appreciation well beyond the U.S., European, and Japanese triumvirate that had dominated earlier editions of the list. In addition to films from India, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, the Top 100 now includes titles from Iran, Senegal, South Korea, and Thailand.

All of these are important developments, and timely ones. Sight & Sound has been discussing the need for greater diversity for decades—since at least 1992, when the list’s lead editorial addressed the fact that it seemed to be guided by a “‘West’ and the ‘rest’” philosophy. But it was not until 2002 that the introduction—this time signed by Ian Christie, the esteemed British film scholar—addressed the workings, the implications, and the limitations of the poll, as well as the larger issue of the canon, in any real depth. “Are [we] voting to reinforce a sense of cinema’s cultural legitimacy or trying to topple a false structure of accepted classics?,” Christie wrote. Then he answered his own question: “Mostly, of course, we’re doing both.” Still, overall, the 2002 poll continued to be characterized by “relative conformity,” as Christie noted. Significant change continued to be put off.

The Criterion Connection

But there’s another factor that should be taken into consideration when examining the canon re-formation that’s currently underway, one that I can break it down in two words: Criterion Collection. I’m being reductive, of course, but there’s little argument that DVD and Blu-ray releases and re-releases play a major role when it comes to deciding which films matter and why these days. As early as 1975, at the advent of the home video era, François Truffaut predicted this outcome—democratizing the ability to own a home library of films would change our understanding of them. Today, there are few organizations that exert as much influence over our taste for film as the Criterion Collection, with its thoughtfully packaged and carefully curated titles.

From the time of its inception in the early 1980s, Criterion was invested in upholding the canon as it had existed up until that time. Among its initial laserdisc releases in 1984 was Citizen Kane, and the company had long associations with Janus Films, the distribution house that was most closely associated with the masterpieces of European and Japanese cinema that were so central to the canon.

Over the last twenty years, through the Criterion Collection, its collection of DVDs and Blu-ray discs, and the Criterion Channel, its online streaming division, the Criterion group has been in the business of both upholding the canon, and tearing it down in order to rebuild it. With nearly 1,200 titles in its list of titles at this point, it’s easy to understand why.

This week, Criterion has been busy touting the fact that over 50 of the films found on Sight & Sound’s 2022 edition of the Greatest Films of All Time can be found in its collection and on its channel. Mere coincidence? Jeanne Dielman was added to the Collection in 2009 in a typically thoughtful two-disc set supervised by Akerman herself. Laura Mulvey, the legendary British film theorist and scholar, has pointed toward “A Nos Amours” [sic], a complete retrospective of Akerman’s work staged in London by Joanna Hogg and Adam Roberts between 2013 and 2015, as being one factor that might help to explain the critical ascent of Jeanne Dielman. But how many critics, programmers, scholars and others were able to attend “A Nos Amours”? And how many gained a new appreciation of Akerman’s work through the Criterion Collection and the Criterion Channel instead?

Teaching Home Economics

One of the most satisfying courses I ever taught was a full-year course on Authorship in the Cinema at Concordia University in Montreal. The course I developed was designed to be an in-depth study of the discourse of auteurism and its impact from 1945 to the present, covering six directors: Jean-Luc Godard, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, and Chantal Akerman in the first term, Douglas Sirk, Jim Jarmusch, and either Todd Haynes or Steven Soderbergh in the second term. Six directors, four films by each. There were many reasons that the course took this form, but one of the primary considerations had to do with DVDs and the quality of the prints they captured. Akerman’s ‘70s films had recently been released by Criterion, while Fassbinder and Godard were already very well represented in the Criterion Collection, as were Sirk, Jarmusch, Soderbergh, and, to a lesser extent, Haynes.

fig. c: home economics as captured in the DVD edition of Jeanne Dielman, 23, qui du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (Criterion Collection)

One of the biggest challenges and greatest pleasures of this course was the module on Akerman. I’d never contemplated teaching Jeanne Dielman before because I’d never had a block of screening time long enough to contain it.*** At Concordia, however, I had a four-hour block to work with, so I was just able to squeeze it in.

My students were quite adventurous in their tastes, but most of them had never experienced anything like Jeanne Dielman. Surprisingly, very few people seem to have researched the film beforehand the first time I screened the film. Attendance was high, and there was no exodus when I started the film 30 minutes later, after an exceedingly brief lecture. During the screening there was some grumbling, some minor signs of frustration, but most of the students stayed till the very end, and, overall, there was very little of the outright animosity that the film had been met with at its premiere as part of the Director’s Fortnight at the Cannes Film Festival in 1975.

Not only that, but there were some students who were utterly blown away by the experience. I even had students who sent me emails in the days that followed saying they’d been so transfixed by Jeanne Dielman that they couldn’t stop thinking about the film. Some said they’d watched again in the days since we screened. One student even wrote me hours later, saying she’d gone straight home and watched Jeanne Dielman again that same night (!). Twice in one day. That doesn’t really happen very often. If it does, my students don’t write to me to tell me that’s what happened. But that’s exactly the kind of film Jeanne Dielman is. Most people who see it will never get it, but those who do….

Akerman reported something similar when Jeanne Dielman played at Cannes. On the occasion of its premiere the atmosphere was “difficult” and Akerman and Delphine Seyrig sat at the back of the theatre watching one audience member after another walk out, their “seats banging” as they left. Within 24 hours Akerman’s life had changed irrevocably. “[Fifty] people invited the film to festivals,” she later recalled. “And I travelled with it all over the world. The next day, I was on the map as a filmmaker but not just any filmmaker. At the age of twenty-five, I was given to understand that I was a great filmmaker.”

O Canada, Where Art Thou?

Finally, you might ask, with all this change in the air, how is Canadian cinema faring? Not particularly well, I’m afraid to say. Not a single Canadian film appears on the Sight & Sound list.**** There’s reason to be hopeful, though. Canadian directors are fairly well represented in the Criterion Collection. Atom Egoyan, Claude Jutra, Guy Maddin, even Allan King—bit of a boys club, but they’re all there.

And with six titles in the Collection, David Cronenberg is a veritable superstar. He’s no Godard (14), but he’s got nearly the same number of films on Criterion’s list as Alfred Hitchcock (8) and Orson Welles (7), and exactly the same number as Chantal Akerman.

aj

*Somehow an exclamation mark seemed inappropriate with this sentence.

**Seyrig’s art cinema credentials are impeccable. They include Alain Resnais’s Last Year at Marienbad (1961) and Muriel (1963), François Truffaut’s Stolen Kisses (1968), Luis Buñuel’s The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972), and Marguerite Duras’s India Song (1975).*****

***When I think back to the days of my undergraduate studies, as well as my M.A., I have no idea how some of my professors pulled off the feats that they did—or convinced us to go along for the ride. I had one course where we watched Hans-Jurgen Syberberg’s Our Hitler: A Film From Germany (1977)—all 7 1/2 hours of it—from beginning to end. I think we did so in two screenings, but still. I had another course where we watched Fassbinder’s Berlin Alexanderplatz (1980)—a 14-episode mini-series that lasts over 15 1/2 hours. Again, we watched it in its entirety, in two particularly epic screenings.

****If it makes you feel better, Jeanne Dielman has a sister in Canada, and her communication with Aunt Fernande, via letter, is a plot element in a film whose plot is otherwise sparse.

*****For the record, every single one of these titles is available from the Criterion Collection.