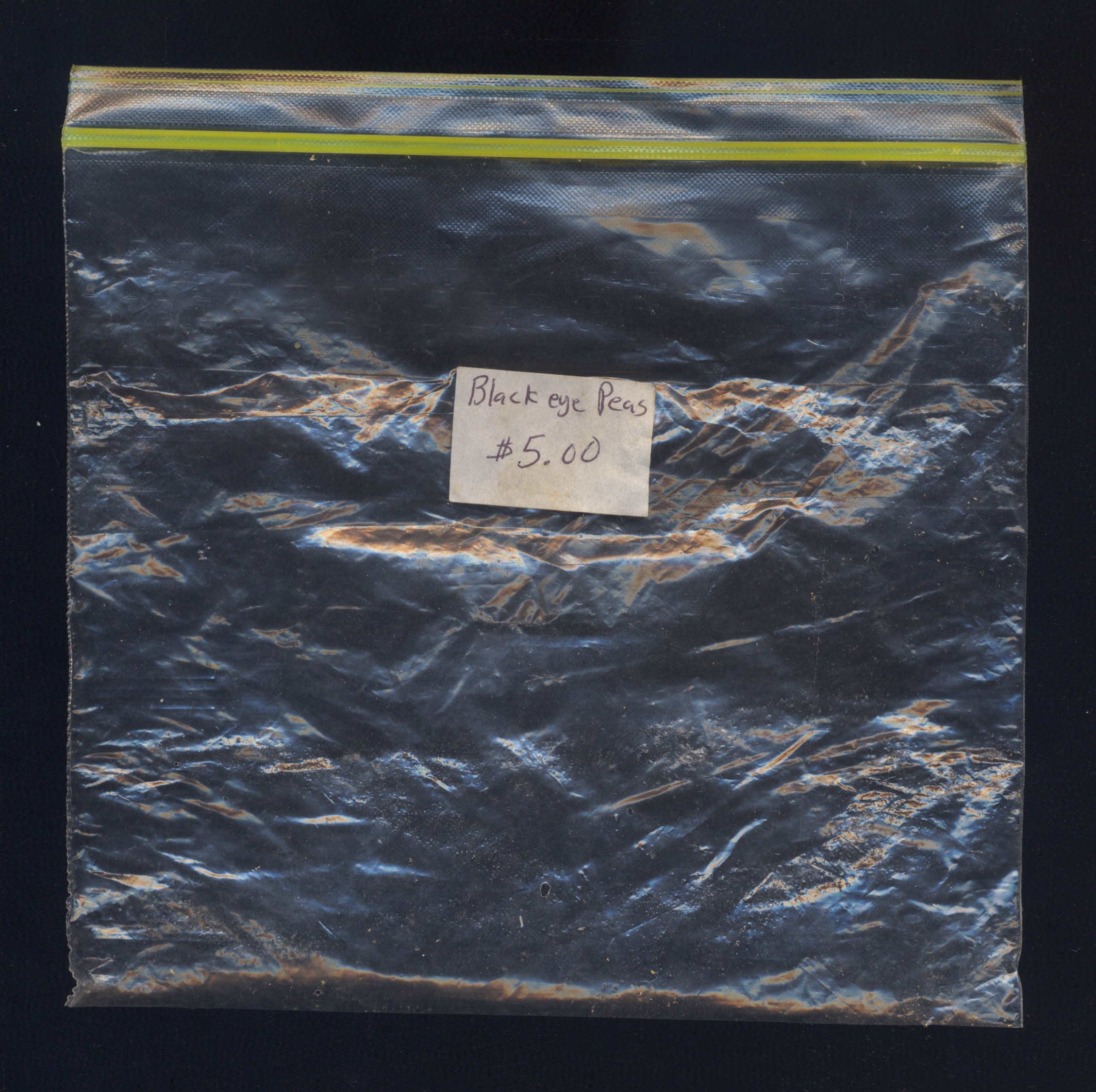

fig. a: the remains of the peas

Hoppin' John is not only the quintessential Southern New Year's dish, and a dish of huge symbolic value in the days leading up to Epiphany. It's also a dish of mythic importance to Southern culture, and especially African-American culture.

The etymology of the name is uncertain. Some claim that "hoppin' John" is a bastardized version of pois à pigeon, especially if one removes the à as one often would when speaking pidgin French (leaving one with "pwaah-peejon"). Pigeon peas were a type of legume brought from Africa to the Americas, and one that was widely used in the Caribbean, where the roots of "hoppin' John" can be traced. Others have come up with all kinds of other dubious explanations, many of which are quite whimsical.* What is certain is that the dish is part of a subset of rice & bean dishes that one finds all across the Caribbean, the American South, and those regions of Latin America that had a slave culture--hence, Brazil's renowned feijoada. What's also certain is that Hoppin' John is quite specifically a product of the Lowcountry regions of North Carolina, Georgia, and especially South Carolina, as well as parts of Louisiana, places where the cultivation of rice was a crucial part of the antebellum economy. You can find variations on Hoppin' John all across the South (and beyond) these days, and the dish has long been a staple of the poor Southern-white tradition Ernest Matthew Mickler called White Trash Cooking, but the dish is of absolutely central importance to the Lowcountry's proud Gullah culture.

John Thorne makes a crucial point about African-American foodways in his masterful chapter on Rice & Beans in Serious Pig. In trying to come to terms with the spiritual significance of Hoppin' John, as well as the level of devotion to it, Thorne writes the following:

To understand the great and poignant imaginative power that has held this dish true to its origins through the centuries, we must first face the fact that when one talks of the foods that slaves "brought with them from Africa," we are allowing ourselves to elide a painful reality. The only thing that Africans brought with them was their memories. If they were fortunate enough to have been taken along with other members of their own community and to stay with them (which rarely happened)--there was also the possibility of reestablishing out of these memories some truncated resemblance of former rituals and customs. But of physical possessions, they had none. [Thorne's emphasis]

Thorne goes on to describe in harrowing detail the passage from Africa to the Americas and the slavers' eventual realization that serving meals that were at least tolerable was essential if they were to successfully deliver their human cargo alive. Gradually, variations on native African dishes were introduced to the meals the slaves were served, including beans, rice, and yams. These gestures were meant to ameliorate the conditions for the slaves just enough that they might make it across the Atlantic without being entirely physically and mentally broken, but they were just that-- gestures. Thorne continues:

[The] hollowness of such self-serving "humanitarianism" can be seen in the slavers' obtuseness regarding the essential component of this diet: the beans.

Instead of the Africans' beloved cowpeas or black-eyed peas, both of which are small, delicate, and sweet, the slavers served them horse-beans, a large, coarsely textured type of fava bean that was used primarily as feed in England. This substitution "exacerbated rather than alleviated the nightmare." When the slaves were eventually reunited with their own peas--not because they were allowed to bring them along on the voyage, but because the slave traders finally started stocking them as provisions--the event was of monumental importance, and held "a sweetness that still reverberates down the centuries."

fig. b: peas & "peacans"

Those reverberation can be felt throughout the city of Charleston and the Lowcountry more generally. You can find variations on Hoppin' John on menus all across the region, and it's a dish whose relative success can make or break a restaurant's reputation. You can also find the dish's essential elements--either black-eyed peas, field peas, or red peas, and Carolina gold rice--everywhere. In December 2013 we came back from the Carolinas with all kinds of mementos, but perhaps the best souvenirs we brought back from Charleston were the black-eyed peas and the field peas we got at Ruke's farm stand. They were certainly the ones that held the most evocative potential--potential that was fully capitalized when we made Hoppin' John ourselves at home.

Because of its particular legacy, Hoppin' John is by definition a humble dish. In its most elemental form, cowpeas or black-eyed peas are cooked with a fatty cut of pork in a simple broth. Raw rice is added at just the right time and allowed to cook fully. Seasonings are minimal, usually consisting of salt and black pepper, salt and red pepper, or all three. Sometimes herbs might be added. Other recipes include an onion and/or some garlic. The peas are not served on rice, the way red beans & rice is served in New Orleans--they're fully integrated. And while it might sound simple, the secret to a truly transcendent Hoppin' John--one that does full justice to its history and traditions--has to do with technique, as well as with ingredients.

It's because of this combination of spirituality and elementalism that Charleston chef extraordinaire Sean Brock places Hoppin' John at the very center of his introduction to Heritage: Recipes and Stories. Hoppin' John is his foundational story. It's his foundational recipe. It's the dish that he claims formed him the most as a chef. It's the dish that holds the key to understanding his Southern cuisine.

And it's because of this combination of spirituality and elementalism that rice & peas will be at the very center of Benjamin "B.J." Dennis' Gullah Nation Feast at the Foodlab this coming Saturday, May 16. Dennis is another highly touted chef from Charleston, and he's been in Toronto this week for the Terroir Symposium. Michelle was wise enough to get in contact with B.J. a few months ago when she heard he was going to be in Canada, and we're lucky that he'll be teaming up with the Foodlab to bring some authentic Lowcountry cuisine to the Lower Main.

Believe me, this guy is not messing around. We picked up his shipment of rice & peas on the weekend and it looked something like this:

fig. c: rice & peas

That's right: 25 pounds. Each.

So, yeah, you can expect some serious Hoppin' John on the menu. You can also expect such Lowcountry classics as oysters & grits, and shrimp with Gullah peanut sauce.

Dennis has established his reputation on his deeply soulful Southern cuisine, and his savvy when it comes to tracing the roots of Gullah cuisine back to the West Indies and West Africa. In fact, in 2014 he prepared a feast he called "From the Land to the Sea" that was designed as just such a culinary voyage. Saturday, he'll be focusing on taking us from Montreal to Charleston. But if you get in the groove, his cuisine might very well take you further.

aj

P.S. Stay tuned for some tried & true Hoppin' John recipes...

* These include:

--an alleged Charleston ritual that involves hopping around a table before a big feast

--the nickname of a Charleston waiter who was famous for his hyperkinetic behaviour

--a guy named John who would get excited and come "a-hoppin'" whenever his wife served rice & peas

--an obscure South Carolina custom that involved the use of the phrase, "hop in, John," whenever a (presumably male) guest was invited over to eat

--Edna Lewis wasn't from the Rice Belt, she was from Virginia, so she didn't claim any special affinity for Hoppin' John. She grew up with black-eyed peas, but only discovered a whole host of other beans and peas when she moved to Charleston for a spell. It was then that she first encountered Hoppin' John, too. She provides yet another version of how the dish received its name in her book In Pursuit of Flavor, one that's particularly blunt: "There is a dish that originated in Charleston called Hoppin' John, which we had never heard of in Virginia. Supposedly, Hoppin' John was a cripple who peddled beans in the streets of Charleston and so a local dish made from red beans and rice was named for him."

and so on...