fig. a: Joan Didion’s California style

Joan Didion’s legend in the kitchen continues to grow and grow.

Stories of her legendary dinner parties have been circulating for years. And when her well-used collection of Le Creuset pots and pans went to auction a couple of years ago, less than a year after her death in December 2021, they raked in $8,000—more than 10 times their estimated value.

Recently, the New York Times bolstered the legend of Saint Joan further, with tales of her extraordinary Thanksgiving parties, where she sometimes entertained as many as 75. The article in question—“Joan Didion’s Thanksgiving: Dinner for 75, Reams of Notes”—was also notable for its attention to the Didion archives (held within the New York Public Library), and the sheer quantity of culinary material that could be found there, as well as to the centrality of the kitchen and of cooking to Didion’s philosophy of life.

Didion appears to have had something of an epiphany sometime between 1964-1965 when she was living in a furnished rental house in coastal Southern California. Many people who came to visit her there were apparently “appalled” by its condition, but the house came with a particularly well-appointed kitchen, including a six-burner stove, a pantry, and a wide variety of “extremely professional pots and pans,” and it was here that she came to the realization, “that a kitchen could be a ritual, a meditation, a room and a time of my own.” She came into her own as a cook during this period, and cooking in a well-outfitted kitchen would remain crucial to Didion’s very being for the rest of her life.

I was impressed by her elaborate dinner parties and the who’s-who of guests they attracted, of course, but I was also impressed by Didion’s earthier more matter-of-fact side, too. Didion was fastidious when it came to typing out her menus no matter how simple. One lunch menu for four from October 12, 1999 read simply: “Shrimp salad, potato chips.”

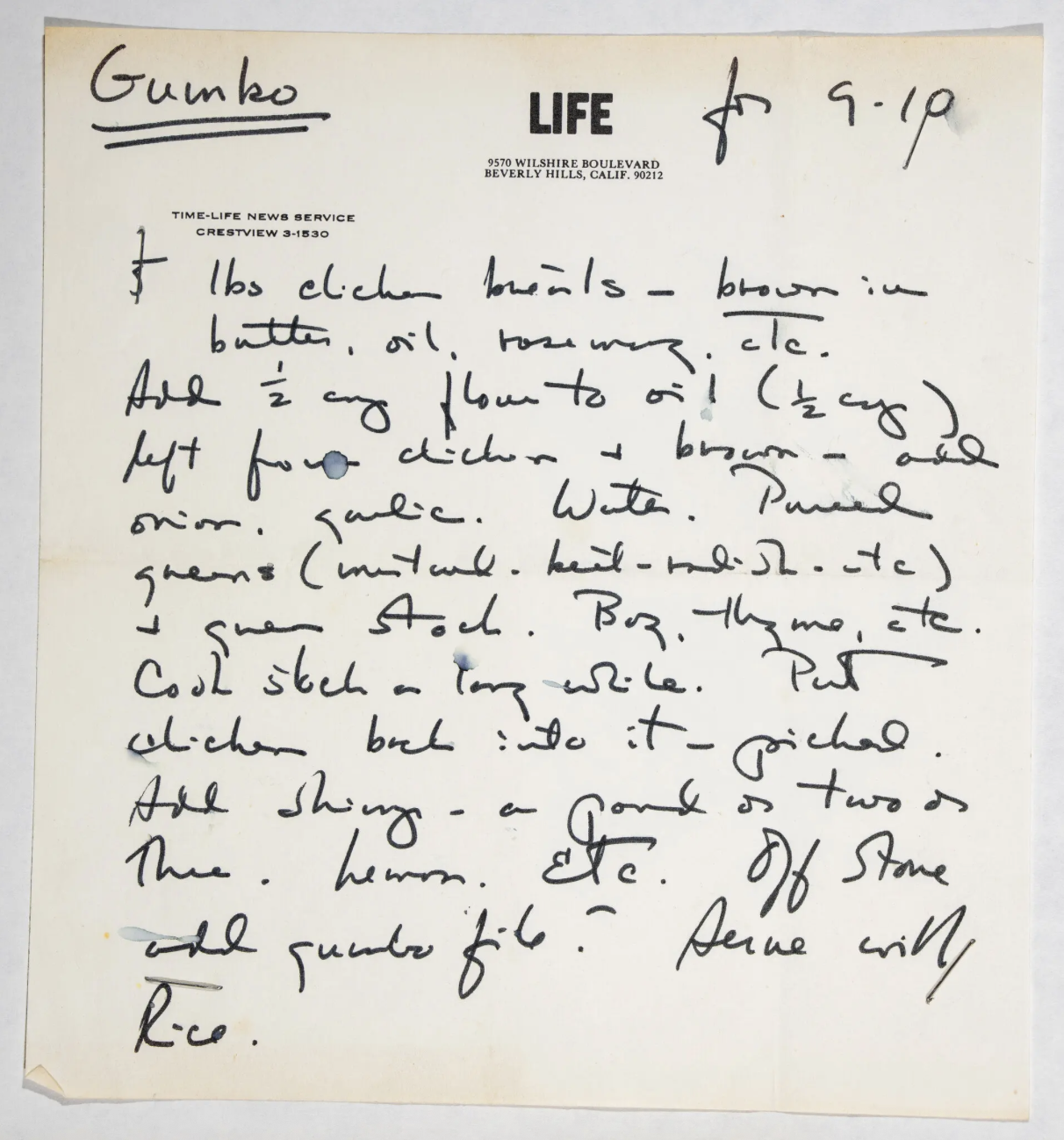

Didion, it turns out, was also a huge fan of gumbo for precisely the same reasons I’m so attracted to the dish: “I like the thrift of it, and the ritual.” Its complex flavours come from the way the dish is prepared, from the method, from the care that goes into it, as well as from the ingredients that go into it. Didion clearly understood the majesty of a true Cajun roux, insisting that it be prepared with a wooden spoon, “until the flour turns the color of a dark pecan.”

fig. b: gumbo à la Joan

Her archives contain several recipes for gumbo, and gumbo was a dish that helped her to articulate her joy of cooking: “Yesterday I made a gumbo, and remembered why I love to cook,” she noted. “Intent is everything, in cooking as in work or faith.” Yes, indeed.

Finally, here are a few tried & true AEB-approved gumbo recipes, for good measure:

Seafood gumbo, 2005

Chicken & Sausage gumbo, 2008

Turkey & Sausage gumbo, 2013

aj